Award Bridget Cooks Exhibiting Blackness African Americans and the American Art Museum

Art historian Bridget R. Cooks didn't know how popular her 2011 book Exhibiting Black: African Americans and the American Art Museum (University of Massachusetts Press) had become until recently, when she found out that, amidst other things, Titus Kaphar had named one of his paintings after it.

An acquaintance professor at the Academy of California – Irvine, where she teaches in the Department of African American Studies and the Department of Fine art History, Cooks had early and often exposure to art museums. She grew up almost the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, worked as a teen at the then new National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C., and had a summer internship at the Oakland Museum.

This deep feel has given her enough of insight into how museums work, not but operationally but psychologically — coded language, community outreach or lack thereof.

Cooks was in Atlanta on March 23rd and gave a compelling presentation to the Spelman Museum Curatorial Studies Program. I sat down with her subsequently to notice out more.

Stephanie Greenbacks: What was the impetus for writing your book Exhibiting Blackness?

Bridget R. Cooks: I worked in a museum as a graduate pupil at the National African American Museum Project, which became the museum that just opened. I was the education intern for the first show we always did, in 1994. That was so long agone. It took then long for the museum to come to fruition. There'd been fighting since the 1930s to try to get a space on the National Mall.

Participating in museum staff meetings, I heard all kinds of discussions about race and social difference that used different terms as a kind of code, like the public and the community , which are 2 different groups of people — the membership , the students , the teachers , the general audience . I was thinking about how these terms were actually coded in terms of race and class in detail. I wanted to exist able to record that in some way that would exist helpful for time to come scholars.

There were three things I noticed that encouraged me to write the book. Ane was the wall labels in museums. If y'all're Black, the characterization states that, but if you lot're white it doesn't say anything. For artists with Asian and Latino backgrounds, their final names unremarkably give away their ethnicity, and so they're not really function of the conversation.

Also, I noticed that when there was an exhibition that included the work of Black artists, the other artists in the show were usually also Black, so there wasn't integration. Yous couldn't just have a thematic mural show, for example, that would include the work of Black artists with work by white artists.

SC: Practice you lot think that's part of the process of getting to a better identify?

BC: Well, information technology has been the process. I don't call up that segregation had to exist the fashion to get to integration. But that's the fashion that it has been historically, mostly because African American artists accept been perceived as a kind of social project to the art world, a group that needs aid. "We're going to do a Blackness show, a kind of social uplift project," instead of having an integrated art-focused project.

SC: In your talk, you mentioned how the Metropolitan Museum of Art didn't desire Black artists to help organize the 1969 exhibition "Harlem on my Heed: Cultural Capital of Blackness America, 1900–1968," namely Romare Bearden, who was offering help.

BC: It'due south difficult to imagine that, because they were then overqualified to help. Romare Bearden went on to co-writer with Harry Henderson A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Nowadays , an encyclopedia of African American artists, and at that point had already written an article on the hereafter of Black artists and co-authored with Carl Holty a volume about structure and composition. He had also sold out his first solo show in New York. With the Met, museum director Thomas Hoving and exhibitions committee managing director Allon Schoener had their own ideas of what they wanted Harlem to be , and that was in their mind . For example, in the beginning iteration of the catalogue — at that place were iv different publications of the aforementioned catalogue — Hoving wrote a story most how he remembered having a Black maid and a Black chauffeur. "Bessie the maid." He knew they were from some other identify he'd never been to.

When he wrote his memoirs, Marking the Mummies Dance , he admitted that he had fabricated it all upward. He never had a Black maid or chauffeur. But the role that he imagined himself to take in relationship to Black people was a relationship of service, and he knew that would reverberate on his own social and economical background. That was actually the driving force: we don't desire the exhibition to be authentic, and nosotros're not really doing this show for y'all, Black artists and Black people in Harlem. We accept our own fantasy of Harlem. They wanted to run across images of racial divergence that they institute comforting. They imagined themselves equally magnanimous and benevolent. People in Harlem had a very unlike idea of who they were, simply it wasn't considered relevant.

SC: Do you think they were white people trying to do good but were just misguided?

BC: That's possible, but lying near the maid was manipulative and unscrupulous. The Met hired African American advisors to exist function of a curating committee that nerveless documents for the prove, but they weren't from Harlem either. I think the advisors wanted to go the prove right, to say to the organizers, you've got to do this a unlike way than what you have in mind , but they didn't want to lose their jobs past pushing too hard. One member of this committee, Reginald McGhee, went on to write an important book about James Van der Zee, who was a prolific photographer in Harlem who by 1960s had become unknown and was poor. His piece of work was rediscovered through "Harlem on My Mind." Deborah Willis wrote the book VanDerZee Photographer: 1886–1983 in 1998 that helped to establish his legacy.

SC: You mentioned that there were three points that prompted you to write the book. Outset was the wall labels, and then Blacks not beingness integrated into shows with white artists.

BC: Tertiary, we had an exhibition at LACMA when I was there in the 1990s, "Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance," and I trained docents and UCLA students to give tours. So when I'd walk around on the tours I'd hear people say things similar "I never knew that there were Black artists," or "This is so wonderful to take this show, we should accept more than shows most Black artists, why haven't they washed one earlier?"

That was an impetus because it encouraged me to figure out how to write down the history so that the volume would exist informative only also helpful similar a reference text.

SC: Did y'all actually just realize how influential it has become?

BC: I really had no idea until I was talking to Mora Beauchamp-Byrd, who's one of the visiting banana professors at Spelman, and she said they were using information technology as part of the curriculum for the curatorial studies plan.

And so Andrea [Barnwell Brownlee, Spelman Museum of Fine Fine art director] said that Titus Kaphar had fabricated a painting using the book's title, so I texted him and he said it'south true. That's the matter, ofttimes yous don't know how the book is making an touch on unless someone tells you. It's an academic book from a university press, then information technology'south non going to sell millions of copies. With academic presses, if you're lucky, the beginning run is one,000. I did sell the first 1,000 within the first year, which is good for an academic book, but it'south not a bestseller. It's not easy to find. You lot accept to be looking for it.

SC: Tell me about the paradigm on the embrace.

BC: I dearest music and I idea of this as my album embrace. I wanted to brand something unique, and I didn't recall there was any one work of art that would be representative of the whole thing. And then I contacted some people at LACMA who wanted to help and I was able to construct this photo in the American galleries. There are 4 of us: my parents are sitting on a bench, my begetter is looking at Homer's Cotton wool Pickers from 1876, then afterwards slavery but the two women who are picking cotton wool were probably sharecroppers. My mother is looking at Mary Cassatt'southward 1880 painting Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child.

SC: Why Cassatt?

BC: I call back it's a very idealized look at maternity. Y'all don't see Black women in arcadian pictures of motherhood. Here's the image [Homer] that'southward bachelor of black, and here'southward the image [Cassatt] that's available of whiteness, the happy mother with her good for you kid. Both paintings are amazing, but if you think of being the African American visitor who looks at this and thinks, hither'due south my place , how much variety and diversity tin nosotros have?

The baby-sit is Abraham Agonafir, who immigrated to this country very well educated only wasn't able to piece of work in his field — he was trained equally an engineer and architect — because of different national standards and licensing, so he had to start all over. He'south likewise a painter. He wanted to work in the U.South., but also be around art and in a place that appealed to his taste. He stands on his anxiety for hours and hours every day telling people where the bathrooms are. He'due south been doing it for over 25 years. He's one of the most elegant soft-spoken intellectual men that I've ever met. The guards wait at the paintings much more than the artists ever did. They spend so much time looking at work but no one asks them what they think, but they retrieve something considering they await at these works mean solar day after day. He agreed to be in the picture.

SC: You also had a lot to say about the "Blackness Male person" exhibition curated by Thelma Aureate when she was a curator at the Whitney.

BC: Many of the artists in the prove weren't Black, but the curator was. One of the points I wanted to make with that chapter is that having a Black curator organizing a testify that has a Black theme doesn't mean that anybody's going to be happy. That'southward non the quick solution. In that location's a lot of diversity of thought among African American people. The exhibition showed a lot of diversity merely there were some artworks that people institute really insensitive. Then in that location was a controversy about the Rodney King video being part of the motion-picture show program.

And so, merely considering Thelma is Black didn't mean she automatically got everything right. That was a really complicated show. My hope is that after reading that chapter we tin can think about the conversations that actually need to happen instead of maxim "nosotros're going to hire Thelma and let her do anything she wants, and we don't have to be responsible as the white administration." Everyone needs to be a office of this conversation.

SC: What are some of the conversations that demand to be had?

BC: There should exist conversations between local artists and museums. At that place are many fine art worlds and I think that mainstream museums often don't admit that. They use words like "quality" to endeavour to make stardom between the kind of art they deem worth buying for a permanent collection and work that's not. If museums get public funding, they do have a responsibility to heed and appoint their local communities. Museums need to retrieve about their collection — what volition we buy and when and how volition we testify information technology?

SC: Right, and while a lot of work stays in storage, someone makes the decisions about what to show. At that place'south also been some criticism nigh how the African fine art galleries in museums are oftentimes on the lower level. Tin can you speak to that?

BC: Placement is something to consider, even if it's for practical reasons. If works are really heavy, nosotros have to accept them on the everyman exhibition floor. The National Gallery of Fine art had "Art of the Aboriginal Olmecs," and those heads weighed iv tons and had to be placed on a floor that could support them. That wasn't a conclusion most the civilization not being seen as relevant.

There are some more obvious means that placement is questionable. Like at MOMA, there accept been works by African American artists that are underneath the staircase on the style to the bath. Why did someone put them at that place? Museums shouldn't exist defensive about it but more thoughtful and anticipatory about what that may say.

SC: There have been a number of incidents in the news lately that have raised questions about who owns which culture and who can tell which stories — the Dana Schutz Open Casket controversy and Kelley Walker's show at the Contemporary Arts Museum in St. Louis.

BC: I'g not compelled to request censorship. I'm fascinated by the fact that the artist is non taking the work down. If I exercise anything that legitimately offends someone, I'grand going to apologize and rethink what I did. That's just how I was raised. I endeavour to be as thoughtful as possible so that I never get into that kind of state of affairs.

I think that the concerns in Hannah Black'southward letter make sense and I'm proud of the artist and the customs who have been artistic in responding to the piece of work in legitimate means, like by blocking people'southward view. It's not shooting, it'southward not killing. It's a much more thoughtful, provocative, serious, and meditative way to try to become people to think well-nigh what they're doing. So information technology is surprising to me that the creative person doesn't say "I totally fucked upward. I wasn't thinking about it in this style, but you are, so I'm taking information technology out."

SC: Practise yous think that only Black people should be able to describe something like that? If a Black person had done that, how would it read differently?

BC: I remember it depends. I remember the issue for the protestors is virtually Black pain. It'due south nigh trying to articulate Black pain for profit. It does help her reputation as an artist, certainly non with some people, just the publicity boosts her career. As an African American person, I observe it totally bizarre that someone would exercise this and say, oh, I never considered what it would exist similar to be Blackness and look at my work .

SC: Do you know the piece of work of Jeanine Michna-Bales? She recently had a evidence at Arnika Dawkins about the Hole-and-corner Railroad. The work is strong, but she's white, and at the opening the question came up of whether she was the right person to be telling this story.

BC: I don't call back that you lot take to be Black to make supportive commentary on the need for Blackness freedom. I'd similar to hear more than people who aren't Black clear the need for Black freedom. It is important for artists to exist able to articulate why they're doing this piece of work. That was one of the issues with Kelley Walker in St. Louis. He had nothing to say at the creative person talk and was even dismissive.

We all know of people like Grace Lee Boggs , the Chinese American social activist and advocate for issues affecting Blacks. No ane is going to say, she can't do this, she'southward Chinese American . We don't accept plenty models for that. I'm hoping that in these conversations amid museums, artists, and the public they'll be able to actually clear what'south at stake and even use therapy language, similar, "when you put your painting upward, it makes me feel similar this…" Let's just effort to observe some language to get it out there. It's like when a news anchor says something racist on network news so gets fired. Okay, what happened at that place? Does he know why he got fired? What about his thinking? Where did that come from? Can nosotros do something productive with this?

SC: A recent example hither in Atlanta was the "Art AIDS America" exhibition at the Zuckerman, which started in Tacoma. The organizers in Tacoma received a lot of flak for not including plenty Black artists. So when information technology came here, the Zuckerman curators were proactive and added works to accost those shortcomings. They added the video by Marlon Riggs, for example, a seminal work from that period that had been left out.

BC: That should be allowed. That'due south a way of showing a delivery, a way of proverb, hey, we want to do this ameliorate. Educate usa.

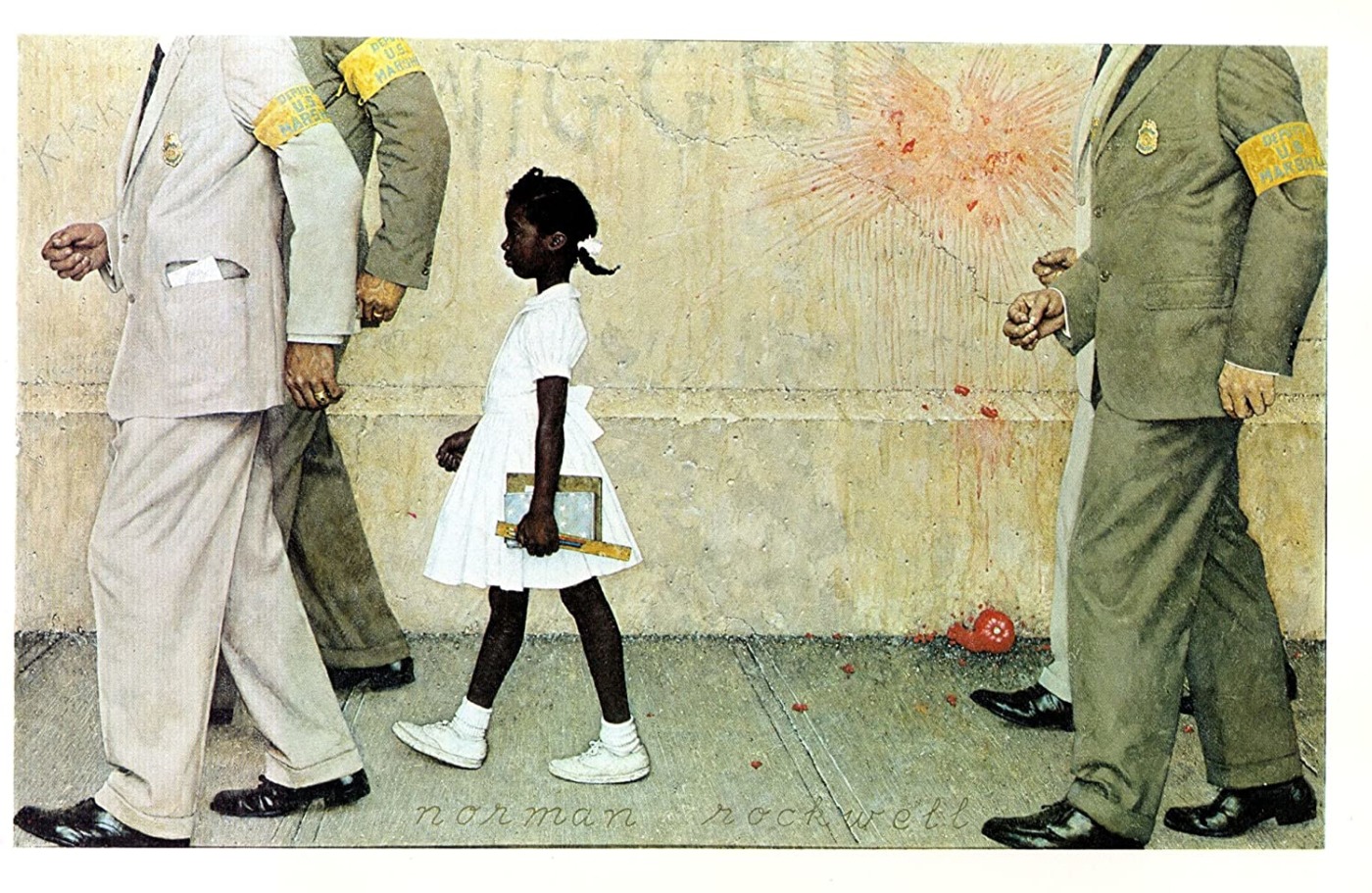

I used to write near the "Without Sanctuary" prove of lynching photos. I felt like it was my job but I had to stop considering I was having nightmares. So I started writing most Norman Rockwell. My side by side book is about his civil rights paintings. The book is tentatively chosen A Dream Deferred: Art and the Civil Rights Movement and the Limits of Liberalism . I'm looking at how ideas of civil rights and Black equality entered into popular visual culture in the '50s and '60s. When Rockwell left the Saturday Evening Post he went to work for LOOK magazine on commission because he wanted to address some of the social ills of America. He did iv very interesting and moving paintings. Look published 3 and rejected the last 1.

My kickoff book was about things that were in museums; the 2nd book is things that were never in museums. So I'll take 2 capacity virtually images that were put on jazz anthology covers, from Abstract Expressionist paintings to portraits of Black men. To call up about how these beautiful portraits — of John Coltrane, Miles Davis — looking at them as very attractive intellectuals existed at the same time that we take images of Blacks being attacked by dogs and water hoses. I'm arguing that these are 2 different kinds of photography. They're using different approaches to civil rights.

Then I'll look at Chris McNair's photographs. He'due south based in Birmingham and in his 80s now and suffering from dementia. He was subsequently known as a politico and went to jail for taking bribes, and Obama pardoned him considering of his medical condition. Most people now don't know him equally a photographer. I'm looking at where his photos were published.

I wrote an commodity based on the Rockwell chapter in Cultural Critique about The Problem We All Live With, which is the painting with the little girl walking in front of the wall with two Federal Marshals on either side. The marshals don't have heads. At that place's no way a Black artist in 1964 could publish an image of four beheaded white men and a little Black girl. Rockwell got death threats for painting that.

Source: https://burnaway.org/magazine/bridget-cooks-exhibiting-blackness-art-museums/

0 Response to "Award Bridget Cooks Exhibiting Blackness African Americans and the American Art Museum"

Post a Comment